Why African Universities Must Shift from Knowledge Mining to AI-Enabled Thinking, Innovation, and Real-World Impact.

I read with dismay the anxiety gripping many world leaders, and

most loudly, educationists in African universities, who argue that the growing

reliance on artificial intelligence (AI) among university students is eroding

critical thinking skills. They insist that critical thinking forms the

cornerstone of higher education. That much is true. What is troubling, however,

is the assumption that AI undermines thinking rather than enhancing it. This

posture reflects a deeper misunderstanding about the evolving role of

universities in an AI-driven world.

Their fear reminds me of my 80-year-old statistics professor, Seregeiv Kazorov

(RIP), at what was then Odessa State University of Economics in Ukraine. By the

time computers had become common tools for statistical analysis, age had taken

its toll on him. He kept his distance from computers—not because he could not

understand them, but because he lacked familiarity and confidence around them. Yet

he interpreted the computer output and made perfect sense of it. His brilliance

was not diminished by the machine; rather, the machine only extended his

capabilities. It is this spirit of embracing tools that seems absent in today’s

fearful university leadership.

The paranoia displayed by many African university leaders brings to mind Robert

Kiyosaki’s famous analogy in Rich Dad Poor Dad: if you place before

a monkey both bananas and a pile of money, the monkey will instinctively choose

the bananas, unaware that the money could buy unending bananas. Kiyosaki’s view

can be used to explain why many graduates choose salaried jobs over

entrepreneurship—they see the immediate comfort of employment and fail to

recognize the long-term wealth-creating potential of business ownership. But

they are not to blame, rather, universities which emphasizes cognitive rather

than application domain.

In the same way, our university leaders cling to traditional knowledge-mining, lectures,

note-taking, memorization, and long thesis writing, while ignoring the

transformative potential of AI. They see AI as a threat to their familiar

academic processes rather than the powerful intellectual engine it is. They

remain unaware that AI can help produce more knowledge, faster, more interactively,

and with far greater depth than any library or supervisor alone can offer.

The core problem, however, is simple: they still believe that the

university’s primary function is knowledge acquisition. But AI has already

relegated that function. Today, knowledge is abundant, instant, and automated.

The true value of higher education has shifted from knowledge mining to knowledge synthesis and application.

That is the new frontier. And yet, our universities continue to insist on

1,000-page PhD theses full of mined knowledge but devoid of real-world

application. This devotion to outdated academic rituals shows just how far

behind the times our Makereres have fallen.

My own experience illustrates this shift. I began my PhD journey at Makerere

University, but after securing a partial scholarship, I completed it

elsewhere—at a university that offered a project-based, product-based PhD, rather than the traditional

thesis-heavy model. I gladly abandoned the thesis-only path and embraced the

product-based approach, which aligned with my vision for the impactful action

research.

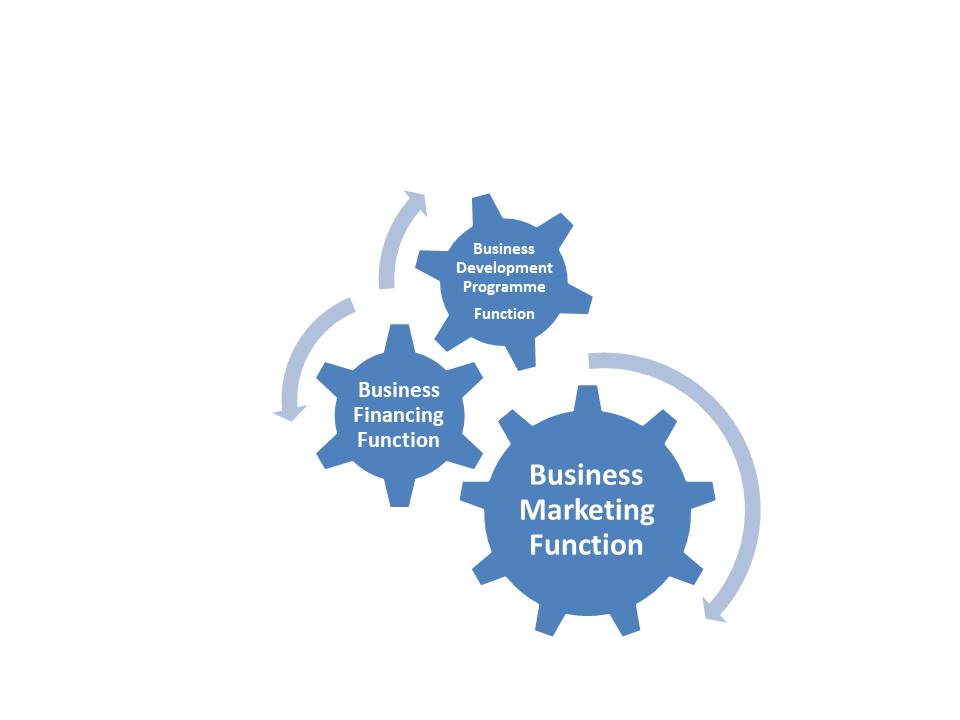

The product of my PhD is Global

University Business Club Limited (GUBCCo)—an ambitious, practical, and

rigorous initiative designed to address Uganda’s disheartening and worsening

graduate unemployment crisis. Whereas most academic works in the current

Makereres are merely into decorating library shelves, my PhD produced a

solution-oriented enterprise. I have presented GUBCCo to our universities,

including our premier Makerere—because charity begins at home—and to Kampala

University International (KUI) as well as to government institutions. Yet they

have chosen to keep their heads buried in the sand, unable or unwilling to

recognize the power of this initiative to meaningfully address graduate

unemployment in the Country.

This resistance is exactly the same resistance now being directed at AI. It is

a refusal to embrace new tools simply because they disrupt old thinking

patterns and institutional habits.

A case in point is the view expressed by Prof. Peter Msolla, Vice Chancellor of

Kampala International University in Tanzania (KIUT), who recently urged

universities to resist over-reliance on AI and to remain anchored in traditional

knowledge-mining methods (https://opr.news/eb86045251211en_ug?link=1&client=news). But insisting on

mining knowledge manually in the age of AI is like expecting an African

bachelor who has now married to continue cooking all his meals himself, or

expecting women to continue using millstones after grain mills have been

invented. Technology does not replace human value—it enhances human capacity.

AI is not the enemy of critical thinking. Rather, it challenges us to raise the

level of critical thinking demanded of students. When machines can gather

information in seconds, the real intellectual task becomes interpreting,

synthesizing, innovating, and applying that information. This is precisely the

shift that our African Makereres are afraid to make.

Instead of resisting AI, universities should redesign their curricula around

its strengths. They should place less emphasis on reproducing facts and more on

problem-solving, creativity, innovation, design thinking, and entrepreneurial

application. They should reward research that produces usable solutions, not

just voluminous documentation. And they should see AI as a partner in learning not

a threat.

The future belongs to universities that can pivot from knowledge mining to

knowledge creation and application. African institutions that cling to old

models risk irrelevance. Those that embrace AI-driven learning will produce

graduates who not only think critically but also create products, enterprises,

and solutions—a case is GUBCCo, which was found as living laboratory for an

action research PhD.

The question is not whether AI will reshape higher education. It already has. The

question is whether our universities will evolve—or be left behind.

By

Dr. Julius Babyetsiza

Founder GUBCCo.